#carbon #fluegas #netzero #sustainability #carbonfootprint

Industrial Energy Optimisation in the Age of Carbon Pricing

Carbon Is No Longer Free

The EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) — the world’s largest compliance carbon market — covers power generation and major industrial sectors across Europe. In recent years, carbon prices within the EU ETS have frequently ranged between €70 and €100 per tonne. For energy-intensive industries, that is not a symbolic number; it directly affects production cost.

The UK ETS follows a similar framework, while China’s national ETS, currently the largest by covered emissions, applies to the power sector and is expanding gradually. These systems indicate that carbon pricing is not a regional experiment — it is becoming embedded in industrial policy.

Trade-linked mechanisms such as the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) extend this logic further. Exporters of carbon-intensive goods into the EU must account for embedded emissions, effectively carrying carbon cost into global trade. Carbon exposure is no longer confined within national borders.

Globally, more than 70 carbon pricing instruments are either implemented or scheduled, covering an increasing share of emissions. Price levels differ, but the structural direction is consistent: emissions are being monetised.

For combustion-driven systems — boilers, furnaces, gas turbines, biomass plants — the financial equation becomes clear:

Carbon Cost = Emissions × Carbon Price

The Hidden Economics of Combustion Systems

Most industrial energy systems are built around combustion. Whether it is natural gas in a boiler, diesel in a generator, coal in a furnace, or biomass in a thermal plant, the chemistry is consistent: fuel reacts with oxygen, releasing heat and producing carbon dioxide.

- Material loss — CO2 is vented to atmosphere.

- Energy loss — sensible heat leaves with the exhaust gases.

From a thermodynamic perspective, no combustion system operates at 100% efficiency. Stack losses, radiation losses, incomplete heat recovery, and excess air all contribute to reduced thermal efficiency. Even well-optimised industrial boilers may operate in the 80–90% efficiency range, meaning a measurable fraction of fuel input never translates into useful process energy.

Under traditional cost structures, these inefficiencies were largely tolerated. Fuel cost was the dominant variable, and emissions carried limited direct financial consequence.

Under carbon pricing regimes, that changes.

Each tonne of fuel burned produces a predictable quantity of CO2 based on its carbon content. For example, natural gas emits approximately 1.9–2.1 tonnes of CO2 per 1,000 cubic meters combusted, while liquid fuels and coal generate proportionally higher emissions per unit energy.

This creates a direct link between:

- Fuel consumption

- Emissions intensity

- Financial exposure

A system that consumes more fuel per unit output not only pays more for energy — it pays more in carbon cost.

Combustion systems therefore represent both the backbone of industrial operations and a structural exposure point under carbon pricing. What was once considered routine exhaust is now a measurable economic variable tied directly to plant efficiency.

How Carbon Pricing Reshapes ROI Models

If the payback extended beyond internal thresholds, it was deferred.

Carbon pricing alters that calculation.

The financial equation expands:

Total Operating Impact = Fuel Cost + Carbon Cost

This changes how optimisation projects are evaluated.

A system that reduces fuel consumption now delivers dual savings:

- Lower energy expenditure

- Lower carbon liability

As a result, projects that previously appeared marginal can shift into viable territory. Even moderate reductions in emissions intensity may have a measurable impact on annual operating cost when multiplied across high-throughput industrial facilities.

From a financial modelling perspective, carbon pricing introduces a new sensitivity variable. Project viability becomes partially dependent on carbon price trajectories, which can fluctuate based on market or regulatory developments. This volatility increases exposure for inefficient systems and strengthens the case for structural efficiency improvements.

In practical terms, carbon pricing does not automatically justify every optimisation investment. It does, however, compress payback periods and improve NPV where emissions reductions are material.

Emissions intensity is no longer just an environmental metric.

It is a financial parameter embedded in capital allocation decisions.

Energy Optimisation as Quantifiable Cost Reduction

Under carbon pricing regimes, operating cost volatility is no longer driven solely by fuel markets. It is influenced by two linked variables: fuel consumption and emissions intensity.

Where fuel use rises, carbon exposure rises proportionally.

Improving efficiency therefore delivers compounded financial impact.

The first lever is specific fuel consumption. Reducing excess air, optimising burner performance, improving air–fuel ratio control, and minimising unburnt losses all reduce fuel input per unit of useful heat. Even a 1–2% improvement in combustion efficiency can produce substantial savings in high-throughput industrial plants operating continuously.

The second lever is thermal efficiency at system level. Stack losses remain one of the largest inefficiencies in boilers and furnaces. High exhaust temperatures represent unrecovered enthalpy. Economisers, heat exchangers, and process heat integration can lower stack temperature and improve overall heat utilisation.

Every unit of recovered heat reduces incremental fuel demand.

Lower emissions → fewer allowances required or lower tax payable.

The relationship is linear. There is no abstraction in the calculation.

Energy optimisation therefore acts as structural cost discipline. It reduces fuel expenditure, stabilises exposure to carbon price fluctuations, and improves cost predictability.

In environments where carbon pricing is embedded in industrial policy, efficiency is no longer a marginal improvement initiative. It is a financial control variable.

Technical Constraint: Dilute CO2 in Flue Gas

If combustion systems are the primary source of industrial emissions, why has large-scale post-combustion capture not been universally adopted?

The answer lies in concentration.

Dilution is the core technical constraint.

Purification adds further complexity. Flue gas may contain:

- Moisture

- Particulates (depending on fuel)

- Trace NOx or SOx

- Residual oxygen

Combustion flue gas presented a different challenge.

Once concentration rises to above 90–95%, compression energy per tonne decreases, purification becomes more efficient, and integration with standard recovery processes becomes technically and financially viable.

Overcoming dilution is not a minor optimisation step.

Integrated Capture and Energy Recovery Systems

Addressing dilute flue gas requires more than incremental optimisation. It demands a transition from standalone recovery units to integrated carbon management systems.

However, capture alone does not define the next generation of systems.

Integrated designs increasingly combine carbon capture with energy recovery, recognising that flue gas contains both material and thermal value. Heat integration within the capture process can support:

- Steam generation

- Refrigeration loads

- Power recovery configurations

This reduces net energy consumption and improves total plant efficiency. Under carbon pricing regimes, such integration strengthens the financial case by lowering both emissions intensity and operating cost simultaneously.

Among established technology providers, Hypro represents a notable example of this integrated transition. With nearly three decades of experience in designing and manufacturing CO2 recovery plants, Hypro has supplied systems to major industrial players across fermentation, chemical, and process industries worldwide.

Building on that foundation, Hypro has now extended its capability beyond conventional high-concentration sources to develop a comprehensive flue gas recovery solution — beginning at carbon capture itself.

Importantly, the solution is not limited to carbon recovery. It is structured to integrate energy utilisation pathways — including generation of power, steam, and refrigeration — depending on plant configuration and operational objectives. This ensures that carbon capture does not operate as an isolated compliance unit, but as part of the plant’s broader energy optimisation framework.

When a well-reputed manufacturer with long-standing industrial references expands its engineering scope into post-combustion carbon capture with integrated energy recovery, it reflects strategic progression built on proven recovery expertise. For asset owners, this continuity of experience reduces implementation risk and reinforces confidence in performance, reliability, and long-term operability.

Strategic Implications for Industrial Leaders

For long-life assets — boilers, furnaces, thermal systems — this has direct implications.

Retrofit vs Greenfield

Existing plants must evaluate whether efficiency upgrades and carbon capture integration can reduce long-term exposure. In many cases, incremental retrofits may improve emissions intensity without major disruption.

For new facilities, the consideration is more fundamental. Designing with carbon integration in mind — from flue gas routing to heat recovery architecture — avoids future redesign costs and operational constraints.

Asset lifespan often exceeds regulatory cycles. Engineering decisions made today will operate under tomorrow’s carbon pricing conditions.

Competitive Positioning

Lower emissions intensity translates into lower carbon cost per unit of output.

Under mechanisms such as the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), embedded carbon content affects export competitiveness. Industrial products with higher emissions intensity may face structural disadvantages in regulated markets.

Energy efficiency and carbon optimisation therefore move beyond compliance. They influence margin stability and market access.

Cost Predictability and Risk Discipline

Carbon markets have demonstrated price variability. Facilities operating with high emissions intensity experience amplified exposure.

Reducing fuel consumption, improving efficiency, and integrating capture systems provide a degree of insulation against both fuel price and carbon price fluctuations.

The benefit is measurable: improved cost predictability.

Carbon pricing is redefining the economics of industrial energy systems. Emissions are no longer external factors; they are embedded in operating cost and capital planning.

In this environment, energy optimisation and integrated carbon management are not discretionary upgrades. They are structural, engineering-led responses to a priced emission framework.

Industrial energy optimisation in the age of carbon pricing is not a sustainability narrative. It is a financial and engineering discipline.

Facilities that align combustion efficiency, carbon capture, and energy recovery within a unified system will operate with stronger cost predictability, greater resilience, and improved competitive positioning in increasingly regulated markets.

Related Posts

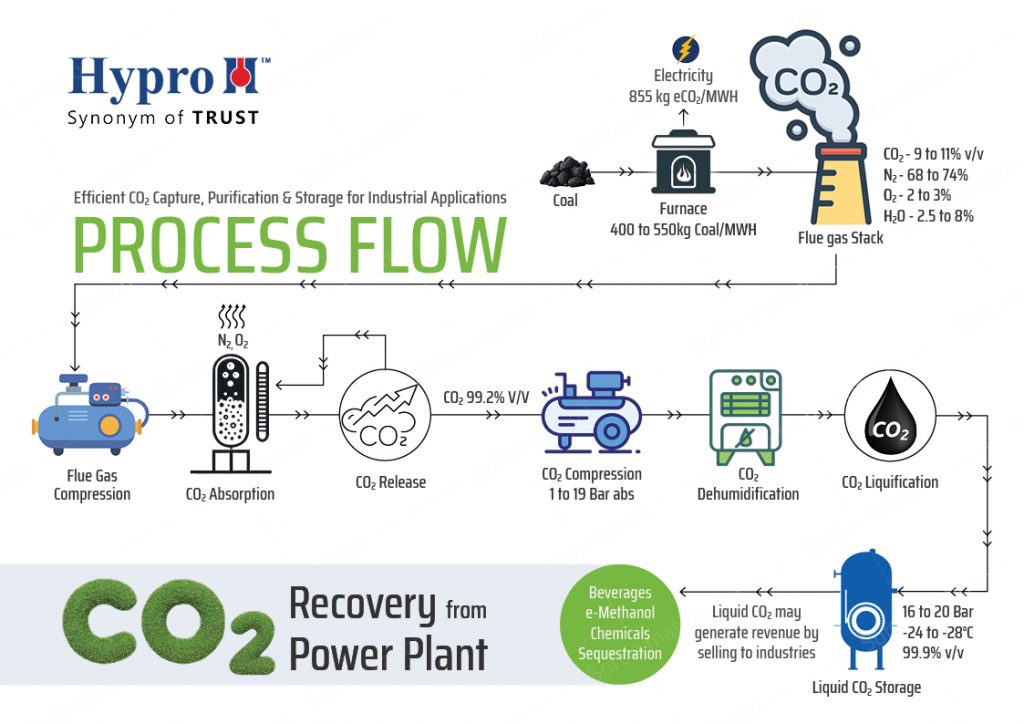

CO2 Recovery Power Plant

Power plants are among the biggest CO₂ emitters, but what if they could turn pollution into profit? With advanced CO₂ recovery technology, emissions can become...

Read MoreEngineering Sustainability

Hypro believes Earth Day is more than a moment - it’s a mission. From sustainability-driven innovations to CO₂ recovery and digital transformation, discover how Hypro...

Read MoreCoal-fired Power Plant Emissions Control

Coal-fired power still underpins over a third of global electricity - but today’s plants face an urgent choice: retrofit or retire. Our latest insights reveal...

Read MoreEnvironment First

On the World Environment Day, Hypro redefines the role of industry - not as a force that extracts, but as one that restores. With over...

Read More